About Late Babylonian Signs (LaBaSi)

Introduction to LaBaSi

Motivation

Although there is a crude distinction between Old-, Middle- and Neo/Late-Babylonian and Old-, Middle- and Neo-Assyrian scripts, each lasting for several hundred years, cuneiform palaeography has been conspicuously neglected as an empirical tool. Pertinent scholarly output has been confined to studies of preliminary character investigating regional or diachronic variations in sign shape on the basis of selected corpora. Compared to alphabetic scripts, cuneiform displays a relatively high number of features pertinent to the ductus of the script. Ductus can be defined as “the order and direction of the traces in the configurations required for the basic shapes of the letters in a particular script” which can be objectified and analysed. A list given by P. Daniels 1995: 82 with no claims to being exhaustive comprises stylus, stylus angle, depth of impression, basic wedges, basic wedge clusters, order of wedges, number of wedges per sign, relative size of signs, horizontal distribution of signs, lengthening of horizontal strokes (see Edzard 1976-80, 545b, who distinguishes between Griffeleindruck and Strich), horizontal and vertical sign alignment, distribution of text on tablet: some of the criteria for defining a “ductus” can be identified on, and are linked to, the level of individual signs; others, such as the stylus angle, are particular to all signs on a tablet or pertaining to a certain type of script. To this one can add the use of ligatures as well as a description of the single wedges making up a given sign as conditioned by writing material (Powell 1981: 426-431).

Workflow

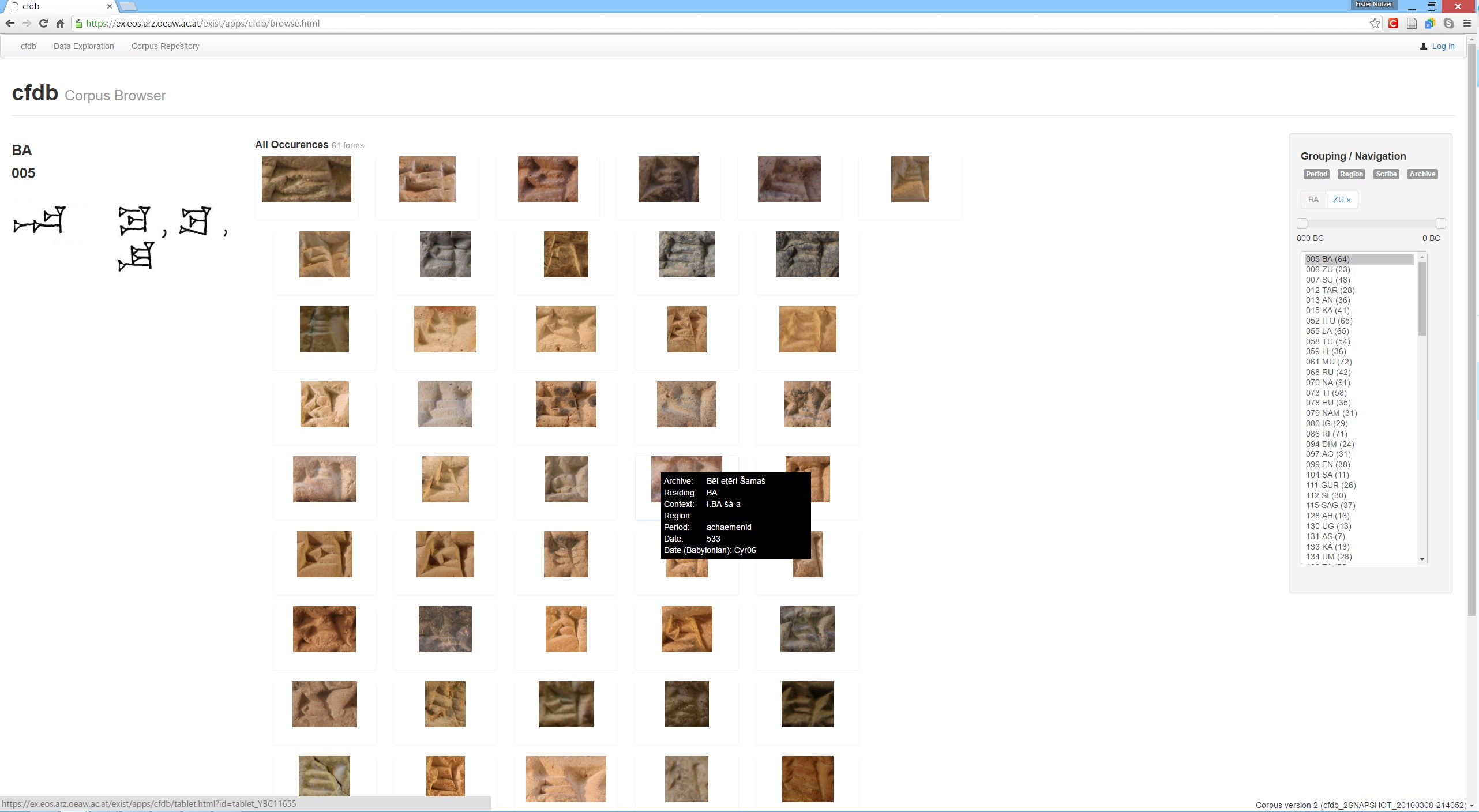

LaBaSi is intended to serve as a research and teaching tool, allowing easy access to the palaeographic information that is relevant for the study of Babylonian socio-economic texts of the first millennium BCE. The principal interest of the website is the identification of standard (or most common) sign forms for first millennium CB cuneiform texts from Babylonia by means of gathering cumulative evidence that can make a claim to being representative of the corpus.

- The first step of the work process was the compilation of a database of digital photographs of a representative sample of tablets. Geographically, LaBaSi stretches from Uruk and Larsa in southern Babylonia, vie Nippur in central Babylonia, to Babylon, Borsippa and Sippar to the north. The earliest tablets date to the reign of king Nabû-nāṣir in the mid-eight century BC, the latest from the early years of the first century BCE, when Babylonia was under Parthian lordship. The gathering of a material basis for LaBaSi was enabled by the generous collaboration offered by two important museum collections, namely the British Museum, having the largest cuneiform collection world-wide, and the Yale Babylonian collection, with its large number of Neo- and Late Babylonian tablets especially from Uruk.

- In a second step, the tablets were annotated. Relevant information thus provided includes date, place of origin and archival context, name of the scribe and a brief indication of tablet content – in short, metadata which can help identifying diachronic developments or regional/scribal peculiarities in individual signs.

- Next, individual signs were directly extracted from the (annotated) digital photographs and arranged in form of a traditional sign list. This method has amongst others the advantage that all metadata for the single signs are immediately available. For ease of working with LaBaSi, and in line with Assyriological practice, the sign numbers of both standard sign lists by the late Rykle Borger are provided: the siglum MesZL (+number) refers to the numbers in R. Borger, Mesopotamisches Zeichenlexikon2. AOAT 305. Münster 2011; ABL (+number) to R. Borger, Assyrisch-babylonische Zeichenliste. AOAT 33. Neukirchen-Vluyn 1978. Also, hand drawing of abstracted standard graphemes of the signs as attested in texts from the first millennium were made.

There is of course quite some variation in the number of attestations of individual signs. One factor is of course the frequency of a given sign in antiquity. More importantly, there is a deliberate focus on potentially diagnostic signs, i.e. signs that exhibit considerable variations in time and/or across different regions. Of some such signs, more than 100 allographs were collected for LaBaSi.

In addition to its employ as a traditional sign list, LaBaSi allows the user to search for sign variants of specific periods, regions, archives and even scribes. Importantly, the possibility of multiple cross-referencing has been accounted for, allowing for the demonstration of interrelations between the several developmental stages of different signs. Consequently, allographs of different diagnostic signs that tend to co-occur can be identified, and a meta-level of general allograph formation detected.

Selection of Studies on Cuneiform Palaeography

There are two important recent collections of essays dealing with different aspects of cuneiform palaeography. The latter covers a longer time frame (from the Early Dynastic Period in the 3rd millennium to the Late Babylonian period in the 6th century BCE), while the focus of the former is on the 2nd millennium BCE and on Syria and Asia Minor, rather than Mesopotamia proper.

- Devecchi, E. (ed.): Palaeography and scribal practices in Syro-Palestine and Anatolia in the Late Bronze Age. PIHANS 119. Leiden 2012

- Devecchi, E, G. G. W. Müller and J. Mynářová (eds.): Current Research on Cuneiform Palaeography. Proceedings of the Workshop at the 60th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Warsaw 2014. Gladbeck 2015

Earlier studies include:

- Biggs, R.: On Regional Cuneiform Handwritings in Third Millennium Mesopotamia. Orientalia 42 (1973): 39-46

- Daniels, P.: “Cuneiform calligraphy”, in: Mattila, R. (ed.): Nineveh, 612 BC. The glory and fall of the Assyrian Empire. Helsinki 1995: 81-90

- Edzard, D. O. Lemma “Keilschrift”. Reallexikon der Assyriologie (RlA) 5 (1976-80): 544-568

- Freydank, H.: „Zur Paläographie der mittelassyrischen Urkunden“, in: Vavroušek, P. And V. Souček (eds.): Šulmu. Papers on the Ancient Near East presented at International conference of Socialist countries. Prag 1988: 73-84

- Klinger, J.: „Zur Paläographie akkadischsprachiger Texte aus Hattuša“, in: Beckman, G. et al. (eds.): Hittite Studies in honor of Harry A. Hoffner Jr. on the occasion of his 65th birthday. Winona Lake (IN) 2003

- Powell, M. A.: Three problems in the history of cuneiform writing: Origins, Direction of Script, Literacy. Visible Language 15/4 (1981): 419-440

- Sallaberger, W.: „Die Entwicklung der Keilschrift in Ebla“, in: Meyer, J.-W. et al. (eds), Beiträge zur Vorderasiatischen Archäologie Winfried Orthmann gewidmet. Frankfurt/Main 2001, 436-445

Texts and archives

Broadly speaking, the material basis for the LaBaSi is constituted by two large groups of texts: archival texts, that is legal and administrative documents, on the one hand, and historiographic, or may better chronographic texts on the other. An exhaustive overview of the extant material is provided by M. Jursa, Neo-Babylonian Legal and Administrative Documents. Typology, Contents and Archives (Guides to the Mesopotamian Textual Records, Volume 1) Münster: Ugarit Verlag 2005. The paragraphs below are neither exhaustive nor representative for the material, but rather serve to give a brief description of the material basis of LaBaSi.

In the first place, the database draws on legal and administrative texts from Babylonia dating from the eighth to second centuries BCE. In fact, there is not very much material from the eighth and early seventh century, but an impressive number of texts is available from the late seventh to the early fifth century. This period between the establishment of the Neo-Babylonian Empire by king Nabopolassar in 626 BCE and the so-called ‘end of archives’ in 484 BCE in the aftermath of two failed revolts against the Achaemenid king Xerxes is now being referred to as the ‘long sixth century’. Thereafter, the documentation subsequently diminishes, and the final centuries of the first millennium BCE are represented by increasingly few tablets from two sites, namely Babylon and Uruk. It should be obvious that the institutional framework of Babylonia (embodied in administrative structures etc.) underwent significant changes throughout the period in question, and as corollary, this holds true for the associated documentary text types, too.

As regards the long sixth century BCE, the most sizable archives from the Neo-Babylonian period are the institutional archives of two temple households. The larger of these is the archive of the Ebabbar temple from the city of Sippar, consisting of roughly 35,000 tablets. These tablets came to light in the course of excavations led by Hormuzd Rassam in the 1880s for the British Museum, where they consequently have been housed since. Second comes the Eanna archive from Uruk, of which ca. 8,000 texts are extant. A significant portion of these tablets came to Europe via the antiquities market – put less candidly, they stem from illicit excavations – and are scattered over a wider range of museum collections, with particularly important dossiers in Yale, Princeton, Paris, London, and Berlin. The Vorderasiatisches Museum also houses those parts of the Eanna archive that were found during the German excavations in the 20th century. Importantly, there are structural differences between Ebabbar and Eanna archives, which manifest themselves in a varying textual record. The former mainly contains primary documents keeping immediate track of the circulation of (not only) agricultural goods and livestock, often in the context of sacrifices, and other valuables, such as precious metals for cultic paraphernalia. Also the various labour and rent and tax obligations owed both by the temple to the crown and by individuals to the temple are meticulously recorded. The archive thus conveys an impression of the temple’s storage facilities day-to-day business. In addition to such administrative texts, the Eanna archive not only contains a considerable number of legal documents, such as trial records emanated from the temple court, but also more secondary accounts, i.e., records compiled from the more ephemeral primary documents.

In addition to temple archives, there is a host of private business archives from all over Babylonia dating to the long sixth century. Typologically, a distinction between entrepreneur and rentier-type activities is sometimes made. The latter are typically members of the traditional urban elites, owning prestigious assets such as real estate in the vicinity of their city of origin and, if belonging to the priestly classes, also temple offices (prebends), which they tend to manage in a conservative manner. In archives of entrepreneurs on the other hand, there is a stronger focus on trade with staple goods, financial intermediation and/or agricultural management on behalf of others, often the temples or the crown. The largest one, consisting of some 1,700 tablets, stems from the capital city of Babylon and traces the dealings of the Egibi family over five generations, thus about a century. Starting out as traders in agricultural goods (onions, dates, wool) on a rather modest scale, they managed to amass an impressive amount of wealth, which they subsequently invested inter alia by acquiring plots of land to be transformed into date orchards, thereby increasing the land’s productivity (and their own revenue). Under the Achaemenids, their economic power translated into political leverage, as by this time the Egibis also managed to gain access to lucrative rent-farming contracts. Usually however, the scope of the archives of such agricultural entrepreneurs is much smaller. An illustrative example is the archive of a certain Iššar-tarībi from Sippar. About twenty-five tablets provide us with snapshots of the career of a merchant without any affiliations to the temple community or the royal administration, but trading mainly in beer and textiles.

Examples for archives of the rentier type include the Bēl-remanni or Šangû-Šamaš A archive from Sippar and the Ilia A archive from Borsippa. Marduk-šumu-ibni, the main protagonist of the latter was active as a prebendary brewer in the service of the Ezida temple of Borsippa, and in addition his family owned a significant number of date orchards near the city which were rented out to tenants. The documentation of Bēl-remanni’s archive is overall quite similar; this archive shows the distinctive feature that it contains also texts relating to scribal education within the family (e.g. in the form of sometimes poorly copied duplicats of economic texts). A particularly interesting archive is the Ṣāhit-ginê A archive, whose chief protagonist Marduk-rēmānni was not only a high-ranking member of the temple community – he held the office of temple scribe, ṭupšar Ebabbar – and owner of multiple prebends, but also an energetic entrepreneur trading in beer and wool.

It has been pointed out above that the documentation at our disposal diminishes significantly after 484 BCE. However, the distinctions between temple and private archives, and in the latter category between entrepreneur and rentier type archives, remain useful heuristic tool. For example, among the tablets found in the Seleucid strata of the Rēš temple in Uruk is a large number of sales of (and service contracts pertaining to) prebends and (mostly urban) real estate, involving the old-established urban elites. The archive of Murašû family from Nippur dating to the last quarter of the fifth century BCE documents the activities of a family of entrepreneurs in rural Babylonia in the Late Achaemenid period. Another relevant archive of this period to be mentioned is the Esangila archive from the city of Babylon, which provides insights into the running of Babylonian temples under first Persian and later Greek overlords.

It is also the libraries of the Esangila to provide us with the second category of text used for this palaeographic database, namely the Astronomical Diaries. These texts are a set of cuneiform tablets recording a variety of observed celestial, climatic, ecological, and economic phenomena, as well as giving accounts of historical events. They comprise the largest collections of observational data available from the Ancient World, consisting of hundreds of tablets dating from ca. 650 – 60 BCE. They have typically been studied by historians of astronomy and economists with a focus on factual content but often disregarding the extrinsic aspects of the tablets themselves. Owing to their coherence and to the fact that a large number of these texts dates to the final centuries of the first millennium, i.e., to a period in which there is a dearth of archival sources, they are a repository of palaeographic information that is still largely untapped.

Department of Near Eastern Studies

Project leaders: Michael Jursa, Reinhard Pirngruber

Research assistants: Matthias Adelhofer, Yuval Levavi

Austrian Centre for Digital Humanities and Culturl Heritage

Developer: Daniel Schopper

Assistant Developers: Peter Andorfer, Ksenia Zaytseva

Logo design: Sandra Lehecka

Department of Oriental Studies - University of Vienna

Spitalgasse 2, Hof 4A-1010 Vienna, Austria

P: +43 1 51581-6101

Email: orientalistik@univie.ac.at

Website: http://orientalistik.univie.ac.at/

Austrian Centre for Digital Humanities and Culturl Heritage (ACDH-CH)

Bäckergasse 13A-1010 Vienna, Austria

Website: https://www.oeaw.ac.at/acdh/